Designing helpful service objects. Part 1. Choosing the right design

I’ve been programming for a long time and I’ve had countless arguments about different things. I’d like to list top four reasons I’ve had an argument online.

Style guide. Thankfully, the number of arguments reduces as I mature, but I’m still spending a lot of time on them. I’d rather have an extremely opinionated styleguide and just stop talking about it. Something like wemake-python-styleguide, but for Ruby.

Monads. I have to admit that this word is almost banned from my vocabulary because of how many arguments I’ve had about it. It’s getting better, but people still like to argue about them. I wrote an article recently about them in hope to show that there’s nothing special to argue about – monads are just abstractions that may or may not be helpful. It all depends on your problems and approaches.

How to design domain logic. It may be an extremely interesting and helpful discussion, or it may turn into a useless argument. When it goes bad, it’s usually because we’re trying to discuss insignificant details and lower-level things. Where do we put arguments? What about dependency injection? How do we use instance variables? Fat model? Service objects? Ughh!

Different interpretation of common terminology. What do we mean when we say “interactor”? What about “architecture”? Is it a state when we’re just passing values from function to function? Is duck typing really an absence of types? What is a type, anyway? What does it mean to write “object oriented” code? What about “functional” approach? Do we need immutability in OO design? Those topics lead to endless discussions with little output.

As much as I love learning about new things, those arguments are extremely energy-draining. They got me thinking: since we’re usually going over the same thing, why don’t we just dump the knowledge somewhere and refer to it instead of arguing? That’s what I’m going to do.

I’m starting a series of blog posts about different topics in Ruby world. My goal is to describe different approaches to the same problems and highlight pros and cons of each one. Perhaps, pick a favorite one and promote it.

Right now I want to focus on two larger topics:

- Designing service objects

- Handling errors in domain logic. Exceptions, values, result objects

This is a first post of the series, and it will cover the first topic: building helpful service objects.

We will go through the basics: what are we talking about when we say “service object”. We’ll look through different approaches and see which ones bring the most benefit and which ones should probably be put to rest. In the end, I’m going to suggest a working design and a couple of guidelines you can use to improve your service object game.

Our main challenge is domain logic

Service object is a common pattern in Ruby community, but you might also see something similar in other languages. Python’s stories were greatly influenced by dry-transactions and Trailblazer — some of the tools we could have used for service objects.

The sole purpose of a service object is to be a place for your domain logic. Remember the usual models vs controllers dilemma? Well, think no more. Complex domain logic goes to service objects.

Let’s step back a little and see why we need to care about the logic at all, and why we should care about its exact location.

Usually, we’re building applications that solve a set of problems for a specific business. Sometimes its logic is trivial, but usually it’s something a sophisticated system that backs a complex business. Sometimes the software is the product that we sell. Either way, the logic becomes complex quite easily.

When we’re modelling complex processes, we have to make a lot of decisions: what needs to be captured in the model; what are the names and processes; what are the boundaries; what’s the shape of our data; how to organize domain logic well. Service objects don’t answer all of our questions, but they nudge us.

Service objects nudge us to organize

When we were working with the common model-view-controller paradigm, we had to make trade-offs and try and design logic using what we’ve got: models and controllers. Concerns, if we’re advanced enough. We put domain logic in the models, application logic in the controllers, and we get our happily ever after.

What if the logic doesn’t fit the model, though? It happens when the relationship is not obvious, or when the process affects multiple models. Here’s a few examples where the solution is not as obvious:

- Does an applicant get a job at a company, or does the company hire the applicant?

- Does a buyer sell the goods, or does the customer buy the goods?

- What if we’re trying to match people by their taste in music? How do we measure it? Is it

jane#compare(john), or is it the other way around? Is it something else? - What if we’re firing someone? Does a manager fire the person? Does the person fire themself? What if HR initiated the process, not the manager? What if it’s a layoff?

Sometimes, the processes in our business are a bit more complex to be reasonably put into a specific model. There are usually different solutions:

Add multiple entry points like Group#add and User#add_to_group. Works best if you’ve found a way to avoid duplication.

Create a new model. It works best if the model matches the real-world domain. It’s reasonable to have a JobApplication which can be accepted or rejected.

Use different models in different contexts. It’s easier to make decisions when we contextualize things. This way, similar entities have different behavior, depending on the context.

Extract the logic into a function / procedure. It feels quite natural to have an option to call hire_candidate.

Note: I've been saying "model" quite a lot. It's not always about ActiveRecord::Model, though. It can be a plain Ruby object or Sequel::Model too.

Service objects nudge us to to the latter – extract the logic into a function or a procedure. Except, we’re using classes and objects instead of “real” functions. Hence the name “service objects”.

It’s not a silver bullet by any chance, but it’s a nice tool which you can combine with other approaches to build better software.

What they look like

Here’s the thing about service object: it’s not really a well-documented pattern. People try to figure out how to design them in a meaningful way, and they get different results. There’s a lot of ways to categorize the service objects, with different level of detail. I’m going to take a shot and categorize by the service object behavior.

The doer is an service object which has the -er suffix in the name. It has a name like OrderCreator, UserRenamer, PurchasePlacer or something similar. This object looks like it’s a person fulfilling their job, and usually doesn’t exist in anyone’s vocabulary, except for the developers. In some cases, it may clash with the terminology as OrderCreator may be both a person who placed the order and a service object. The doer usually has one public method named call, perform, or the one matching its purpose: create, update, assign, etc.

class OrderCreator

def create(...) # or call / perform / etc

...

end

end

The multitool is a service which fulfills many jobs at once. For instance, OrderManager may assign and remove couriers, update delivery dates and even cancel the order. Everything is centered around a specific entity.

class OrderManager

def initialize(order)

...

end

def assign(...)

...

end

def cancel(...)

...

end

def reschedule(...)

...

end

end

The event is a service object which models a process which starts when a specific event occurs. It’s usually a complex multi-step process. The name usually captures the name of the event: ApplicationSubmitted, OrderShipped, UserBlocked, and so on.

class OrderPlaced

def call(...) # or handle / perform / etc

...

end

end

The command is a lot similar to the event, except it’s designed as an imperative action in your domain. The object has a name similar to SubmitApplication, SubmitOrder, BlockUser, etc. It may look like the doer except for one major difference: it has a proper naming. People also call it an “operation”, or even a “use case” or an “interactor”.

class SubmitOrder

def call(...) # or handle / perform / etc

...

end

end

Other service object implementations usually fit within one of those four groups. If I’ve missed out on something, please let me know at [email protected].

I’m going to be blunt and say that you should probably throw away the doer and the multitool and replace them with something else if you’re using them. Let’s see what their problem is:

The doer is like the command, except it has a poor naming. Instead of capturing something real like an action, it’s modelled as if it’s a full-grown entity in your business. In most cases your business does not have a SomethingCreator, but it has an process to CreateSomething. There’s a huge benefit in speaking a natural language instead of inventing your own, so my advise is turn all doers into commands.

The multitool is a nice attempt at a service object, but has a couple of fundamental flaws.

- Similar to the doer, the name doesn’t capture domain pretty well. I’ve seen people choose names like

OrderManagerorOrderService. Neither of those really exists in the domain. - Is it really a “service”, or is it a model in disguise? You may achieve similar level of isolation by extracting the logic to a module / a concern and including it to your model.

While I can totally understand the desire to use this design because it extracts and isolates the logic and makes it feel like everything is better, I’d advise everyone to take a deeper look at their own paradigm and see if there are better tools to solve the same problems.

One of the question you have to ask ourselves: why did we have to stray away from the good old object-oriented model and common Rails ways? Perhaps, we’re better off using approaches described in Eventide’s useful object manifesto, Yegor Bugaenko’s Elegant Objects or Ivan Nemytchenko’s Rails Hurts → Painless Rails. I’m no expert in any of those things, so let’s speak about useful service objects instead.

Why some service objects are more useful than others

In his RubyRussia 2019 talk “The future of dependency management in Ruby” Anton Davydov mentioned the problems with service objects and showed the many ways to use them. When he mentioned the lack of standardization, I knew I wanted to write an overview and highlight the most useful ones, so let’s do it.

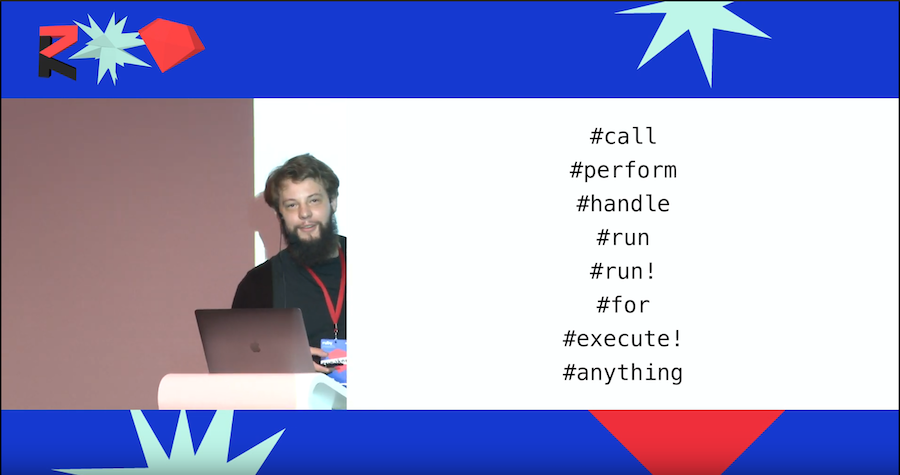

As you can see, there are at least eight popular ways to name the service object’s primary method. It is not really a problem, as you just have to pick whatever works for you and stay consistent about it. I prefer #call, but you might want something else.

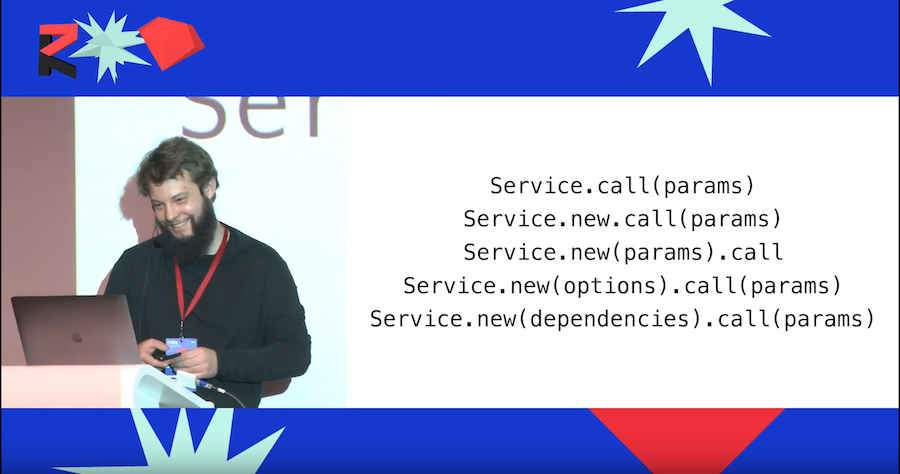

There’s a deeper problem: how do we actually use the objects? How do we build them? Where do we pass the parameters? What about configuration? What about dependencies? Oh my! Just take a look at the many ways to use service objects. The slide covers probably 99% of known service object usages, so kudos to Anton for putting together the list.

Let’s make sure we’re on the same page about terminology before going on.

When we’re talking about params, we’re usually talking about ordinary data that we pass to the object. It’s the same arguments we would normally pass to a method that does something.

Dependencies are a bit more tricky. Usually, our service objects can’t perform a task on their own. They need to know how to retrieve data from the database, how to send an e-mail, how to run some related logic. It’s impractical to implement all of this ourselves, so we delegate it to some external objects, services and modules. Those are the dependencies. They’re the owners of the knowledge.

Options are a bit like dependencies, but simpler. It’s a run-time configuration. Rule of thumb: if you’ve put some magic numbers, strings or other values in a constant, it’s likely one of those options.

Now that we’re clear about shared terminology, let’s speak about the list. I’ve rearranged it and split the items in three groups. The result is heavily opinionated, so I’ll explain it afterwards.

The most helpful service objects are the ones which give you the most power. They’re arguably the most pragmatic ones.

- Service.new(options).call(params)

- Service.new(dependencies).call(params), which is almost the same as the example above

- Service.new.call(params), only if it’s a shorthand for the first two options with reasonable defaults

- Service.call(params), when it’s an instance created via the first three options. i.e.

Service = OtherService.new(...)

Moderately helpful won’t bring you as much benefit, but they’re still decent if you use them well

- Service.call(params), when you just don’t need to instantiate anything. You won’t get the benefit of configuration, dependency injection or anything, but it’s still a decent piece of logic

- Service.new.call(params). It’s not really helpful if you cant’t configure it at all, but oh well. A future-proof design may be helpful though.

Not really helpful are redundant or just poorly designed. You should probably reconsider when you meet one

- Service.new(params).call

- Service.call(params) is bad if it’s just a shorthand for most of the

new.callvariations

This classification is purely opinion-based, yet there’s reasoning behind all this. It’s mostly based on my own experience in software engineering, and a couple of other ideas. It mostly comes from the fact that I like my code to be deterministic and easily modifiable. I’m also a little product-oriented, so I fiddle around with different configuration quite often.

Each object must have a reasonable lifetime. Service objects are essentially complex functions and procedures, and their lifetime should probably be similar to one of any other function, module or class. Even if we’re into OOP, instantiating and object which can only be used once before being discarded seems to go against the general idea. Sure, there are cases where the function lifetime should be short, but those cases require extra thought.

Logic should be easily extendable. Especially if we’re building a start-up which is rapidly evolving. Want to pay your contractors a 10% bonus instead of a usual 5%? Just configure the service and use it. Handy for rapid and cheap experimenting. Want to refund a user even though we normally don’t? Just use the service with a different set of policies. Works best if I don’t have to write any code to customize it.

Code should expose bad design instead of promoting it. Writing an overly complex logic should be possible, yet the code must look and feel overly complex. This way, you’ll be able to improve your design before it becomes too time-consuming to maintain.

No mutable state is a common idea in functional programming and a not-that-common idea in the OOP world. It adds verbosity, but verbosity is not a problem. We’ll get better reusability, testability and composability if we follow the rule.

Services should be composable. It means we should be able to organize them in a nice pipeline to avoid clumsy interfaces. We can achieve it by returning composable values, like result objects, monads and stuff like this.

Our logic should be insighful. The code should help us figure out how the world works. We need to learn about our processes, their limitations and core participants. The complexity of the process, points of pressure, possible bugs and likely mismatch with the real-world domain. The code should help us gather the insights instead of obfsucating them.

That said, I’ve found that I get the most benefit when I’m using a constructor to configure the service object and provide dependencies, and pass the input parameters to the #call itself. It’s a bit more verbose because I have to explicitly declare all dependencies and I have to pass variables around. It brings a great benefit as I can feel that I have to refactor this place when it gets too complex. I also heavily use default dependencies, so I don’t have to be too explicit.

Whenever I feel like there’s no need to configure, or when the team has a different convention, I like to use class methods and avoid instances. This way, I’m still getting the benefits of a good lifetime and I get to expose the overly complex design. This works pretty well too.

Q: why use class methods when you can just use a module?

A: I like to think that modules are meant to be included into your classes, or serve as a namespace. There's nothing wrong with using module methods instead, though.

Other designs, especially the new(params).call have failed to meet my expectations. Its only benefit is that I can utilize instance variables to save myself a few taps. I don’t want to trade off all the benefits for that.

I’ll stick to the new(options/dependencies).call(params), as this is the most powerful way to use service objects. We’re going to dive deeper into the practice in the next part, so here’s the design that I’m promoting:

# A service object which pays a baker a bonus for an order

# It's a command, or an operation

class RewardBaker

attr_reader :bonus_ratio

def initialize(bonus_ratio: )

@bonus_ratio = bonus_ratio

# <= any other dependency / configuration goes here

end

def call(order)

... # <= logic goes here

end

end

reward_baker = RewardBaker.new(bonus_ratio: 0.05) # a 5% bonus is nice

reward_baker.call(other_order)

What’s going to happen next

Service objects are a large enough topic, and I can’t cover them in one post. If I do, only a few people will have the time to read it – it’s going to be too overwhelming. So I’m going to release at least two more parts: “the practice” and “the next level”.

The practice will be a design exercise where we model a business process and illustrate decisions and trade-offs of service objects. It’s going to show how to use the event and the command and why those designs have a name which looks like they come from CQRS, Event-Sourcing or something similar.

In “The next level” I’ll talk about techniques which will help you get more from service objects: reduce boilerplate, organize a pipeline, and gather more insights. Afterwards I’ll address some of the flaws. I’ll finish it with a small guideline on designing service objects. I’ll also address some of my claims about the design decisions.

The rabbit hole

If you want to go down the rabbit hole and discover more yourself, feel free to dig through the resources I’ve mentioned below. Make sure to check the first two articles. They criticize service objects and provide nice alternatives — those may be extremely helpful for you too.

Avdi Grimm highlights the possible problems of service objects and provides alternatives. The “Domain-driven design” part is important, you should totally read it.

Jason Swett wrote a nice piece addressing service objects and their problem.

Toptal has a solid article on service objects which gives some advise on good designs. You may notice that I don’t agree with it, but it’s alright. You may like their reasoning more. Check it out.

Ivan Nemytchenko’s book on Painless Rails. If you like Rails, but not quite, this book might help you improve your game without service objects.

The future of dependency management in Ruby by Anton Davydov

Useful objects manifesto by eventide

Hanami guide has a decent article on the pattern and how to use it.

dry-transactions — a once-popular gem, which used to be deprecated, but right now it’s going throw a rework. It’s a DSL for domain logic, which essentially implements the “service object” and “railway oriented programming” ideas in a nice way

Trailblazer was aimed to simplify our lives and domain logic, and brought a lot of new ideas to Ruby world

How Python devs implemented the idea

Most strict linter for Python. I want something like this in Ruby. Hopefully, Standard will help with that.

Yegor Bugaenko’s blog contains a lot of controversial and thought-provoking content. One of the ideas is that immutable objects should be a default in the object-oriented paradigm.

Yegor Bugaenko wrote a book on his ideas. If you want a different look on OOP, it’s definitely going to help you.

I wrote Should I really use monads? to discuss a smaller topic which comes with service objects: monads. Together those two abstractions enable you to do railway oriented programming, which is nice.

Rob Race’s article on 3 tenets of service objects. It was an interesting read.

Scott Domes shows the ServiceObject.call(args) as a shorthand for new(args).perform in Service objects in Rails.